A postscript on first recipes

- rosemary

- Oct 18, 2023

- 8 min read

As a self-taught cook, I learned through cookbooks and love them dearly. There's an evolution to learning to cook this way and choosing cookbooks. ... In the end each cook has a particular journey and path to follow and cookbooks are wealth of knowledge to pave the way."

Sharon LaFleur/Quora

On the left the first recipe from a fairly recent purchase Extra Good Things from the Ottolenghi Test Kitchen, in the middle is the first recipe I wrote about yesterday from Mietta's Italian Family Recipes and on the right the first page of the first chapter in Elizabeth David's French Provincial Cooking, which I think was my first purchased cookbook. The first recipe in that instance was simply a recipe with no illustrations at all - after the chapter introduction - for Bouillon pour les sauces (stock for sauces). I chose the first page of the chapter rather than the recipe itself because it does at least have a drawing. I've arranged them in reverse, partly because the photograph of the Ottolenghi dish is spectacular enough to hopefully get people to read this post - it's the only one that will show on the blog summary page. You might not choose to read if you were confronted with the Elizabeth David one, which partially says all I am probably going to say here about the importance or not of the first recipe I guess. Besides all three probably show, in reverse, how my cooking has evolved over the years.

There were several reasons why I thought my First Recipe idea would be a good way of getting over the occasional writer's block. The main two reasons were to introduce my cookery book collection, and also to ponder on why a particular recipe had been chosen as the first recipe and whether this choice was good or not. And this, was, in many ways the main idea that I had.

Of course as time has gone by the reason for the recipe being a first recipe has been pushed further and further into the background as I wrote my posts. Well it soon turned out that many of them followed a pattern - stock or a simple entrée. I have mostly talked about the recipe itself, sometimes the author, sometimes the book in general, sometimes a ramble into personal memory, sometimes of all of these things and more. But probably not a lot about why that recipe is the first recipe in the book. Although admittedly sometimes the reason is so obvious it's not worth mentioning.

So far I have, mostly, been wandering through the oldest books in my collection as well. The shelves on that particular bookshelf are smaller, and the old books tend to be small paperbacks - except for the bottom two shelves, where MadhurJaffrey and Charmaine Solomon are to be found. With Mietta I have moved to my central bookcase, which is a bit of old, a bit of new and a bit of in between. With medium sized shelves, so the middle in almost every sense of the word.

Those three books at the top of the page however, illustrate perhaps the evolution of cookbooks as well as my own cooking.

My mother had just one cookbook - Mrs Beeton's grand tome, but she didn't use it very often. Her cooking had been handed down from her mother and she also read magazines. I initially learnt from her of course, with a little bit from school and much more from my French hostesses. Whilst at home I did begin to look at recipes in magazines along with my mother, it was only when I left home that I began to collect cookbooks. How else was I to manage?

The page shown here is from, perhaps my second purchase, and definitely of the same era - the first kind of recipe - not really recipes - more ideas - from Robert Carrier's Great Dishes of the World. This too was mostly just text although it was interspersed with glossy full paged photographs, and so rather more glamorous - in keeping with his persona - than Elizabeth David. And maybe it was those glossy photographs that sold the book.

Back then cookbooks were mostly of the educational kind, because we were all learning to spread our wings in the kitchen. Although of course, every generation is in the same position. Nowadays they learn by watching YouTube videos. And so the arrangement of the books was almost universally either the arrangement of a meal, or the arrangement of the skills - beginning with the simplest and ending with complicated desserts or soufflés. Mostly it was the courses of a meal arrangement, and let's face it, this basic arrangement persists to this day.

It certainly persisted for several years. The only cookbooks I can think of back in those days that were arranged differently were semi-encyclopaedic - like Jane Grigson's Vegetable and Fruit Books - or geographic. The book might be about a particular cuisine with the chapters making a tour around the country, although often they did the tour with an essay on a region, before going back into the normal meal courses pattern - Appetisers, fish, meat, poultry and game, vegetables dessert - I'm sure you recognise this.

However I consumed them all. And I learnt from them. I'm sure I made many more of the dishes in those early books than those from my middle and later period. Even without the pictures. The pictures didn't matter so much, it was the techniques, the tips and tricks, what went with what, that I was after. So perhaps as I learnt I was more able to improvise with what I had. But I did love them and became a fervent collector - always in the hope of learning something new:

"for practical, everyday beauty, for hope, for love, for mind-changing advice, it was always cookbooks." Kate Gibbs/The Guardian

Cookbooks made money for the publishers - some of those early books had massive sales, unimaginable today - well there was not as much competition back then, and the pioneers have continued to be published, so the money still comes in. The demand for cookbooks grew however, and so the publishers had to up their game in order to sell their books, because:

"[They] know that the chances of making money are greater on a cookbook than on a novel." ( in 1961 anyway) Kate Gibbs/The Guardian

And gradually we got more pictures, initially, as occasional glossy photographs of what we were aiming for, and eventually with a picture for every recipe. Not always though. There are the outliers. Like Mietta's book, which although largely text, that text is interspersed with family photographs and each chapter has a stylish opening. Even the recipes themselves, as you can see from the image at the top of the page, are stylishly presented. One recipe per page, however, short, with the ingredients, the method, the introduction and any notes all clearly differentiated. Design is key. In the course of my 'research' on the topic I found a really interesting article by T. Susan Chang an American cookbook reviewer in Publisher's Weekly entitled 10 Things Every Cookbook Publisher Should Know.

One of those things was that the text of the recipe should be clear because:

"They are used as physical objects in a way other books are not. Every time a cook tries a new recipe, she returns to the page at least a dozen times. Format matters" T. Susan Chang/Publisher's Weekly

Sticky fingers need to be taken into account, appropriate measurements, clear explanations, large print ...

Before I leave Mietta, however, and really the starting point for this piece - why did she - or the publisher - chose bagna cáuda as her first recipe? It's clear enough why Antipasto was the first chapter - it's the traditional format. But why bagna cáuda? The second recipe is bruschetta - why not choose that? Momentarily it made me think she had arranged her antipasti in alphabetical order, but no this is not the case. Bagna cáuda is not necessarily something that anyone is going to try after all - controversial anchovies mixed with lots and lots of garlic! You would think that this would put a lot of people off. I have no answer. Other than to say that Giorgio Locatelli - an Italian guru chef of world-wide fame - quotes it as his favourite dish. So maybe it is truly fantastic. I shall never know as we have an anchovy hater in this house. In her brief introduction she doesn't even give a personal reason.

The teaching kind of cookbook still exists - the kind without pictures - but rather more beautifully designed nevertheless. The way you arrange your text can be attractive enough in itself - particularly if you know of the cook who wrote it.

These days however if you are choosing a cookbook from amongst dozens at least, then it's the ones that catch your eye that entice you to buy:

"Good design is essential; good art can make a buyer fall in love with your cookbook right there in the store. But don't let your food stylist go so crazy with the shot that it no longer bears a relationship to what the home cook can reasonably produce."

T. Susan Chang/Publishers Weekly

The OTK example at the top of the page is a shining example - looks amazing, but you can also tell that it's pretty easy. And if you are in a bookshop flicking through you would have to flick through half a dozen recipes before you come across something you are less sure about.

As is this one from a relatively recent Jamie book 7 Ways, in which the idea is to feature 18 ingredients which are big sellers, and provide 7 different ways of cooking them. This one - the first recipe is Easiest broccoli quiche - its title is also carefully chosen to get you in.

And both of these books diverge enormously from the usual arrangement of a cookbook. Well I suppose Jamie fits into the encyclopaedic structure - in a loose kind of way, but the OTK book just goes with different kinds of toppings, although it does succumb to normality by ending with dessert.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder however, is it not? Or rather the reasons why you might choose one cookbook over another may be quite different to mine. Sometimes it's just a fan kind of thing - the when will the next Ottolenghi book be out sort of question. Sometimes you want to learn more about a particular cuisine, sometimes you want to go vegetarian or vegan. Sometimes you just want to drool at dishes that you will never make yourself because they are restaurant fare and beyond your expertise, but the finished book is a masterpiece in itself.

"Design plays a role in making a great cookbook, but for the most part, it's the content that separates the wheat from the chaff. The author of a great cookbook has passion to spare, and a vast fund of knowledge. That shows up in the details, whether they’re technical, historical, scientific, or anecdotal." T. Susan Chang/Publishers Weekly

Not entirely true I think but I will try and focus a bit more on why that first recipe is the first recipe you come to. Claudia Roden is up next with Med and foccacia.

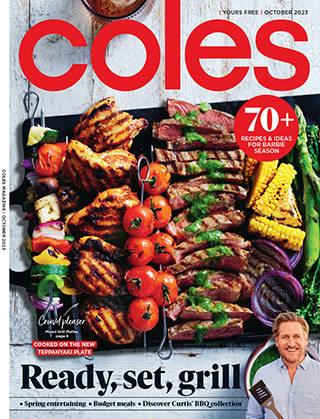

Perhaps I should also consider the choices the magazines make as well - the cover is more important here, although the first recipe is not always the cover. Besides the supermarket magazines are free, and so the same decision process is not being employed. You don't have to choose - you just have to be there at the right time to get one. Here are the current ones - first recipes - the cover recipe for Coles, I do not know for Woolworths - I missed it and can't open it online.

Apologies - this is a bit of a nothing ramble I feel. I guess the thing is I'm not really sure how important that first recipe is. I suspect that not a lot of people focus all of their attention on that. After all you have to find it first. Sometimes you have to flick through a whole lot of introductory matter. And sometimes, yes, it might be just another recipe for chicken stock. I think we are more inclined to flick through the book to see what kind of food is on offer, how the recipes are laid out, who the writer is, whether indeed there is much writing. All manner of reasons. It might just be that it's on a special! But never mind the First Recipe thing does give me a starting point when I'm completely uninspired even if it leads nowhere - like today.

Comments